Safety and Suffering

Is All This Talk of Safety Creating Fragile People?

In conversations about trauma-informed care, I sometimes hear the critique: All this talk of safety is making people fragile!

It comes in different forms:

“We’re raising kids who crumble at the first sign of discomfort.”

“Not everything needs to be labeled trauma—sometimes life is just hard.”

“A little adversity never hurt anyone. It actually builds character.”

“We’re coddling instead of correcting children.”

“We’re creating immature adults who can’t tolerate discomfort.”

“We’re raising a generation without grit.”

And, I understand the concern.

We live in a moment anxious about weakness, suspicious of vulnerability, critical of empathy, and nostalgic for a brute toughness that—from the perspective of some—built character.

But this critique misunderstands what safety actually is—and what it’s for.

Safety is not cultivated to avoid suffering. Safety is what makes it possible to suffer well.

In trauma-informed work, safety is not about hovering, protecting people from every pain, or insulating them from reality. It’s about creating the inner and relational conditions that allow a person to face reality without being overwhelmed by it. Safety does not eliminate suffering; it gives suffering somewhere to land.

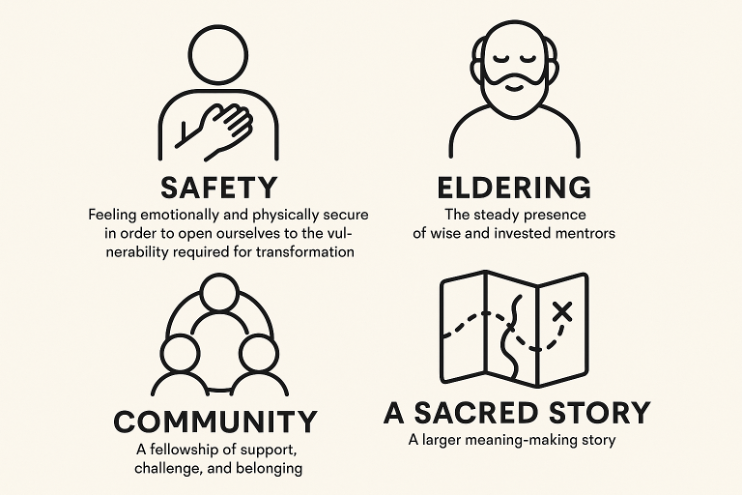

Two decades ago while doing my PhD work, I discovered Michael Gurian’s research, writing on male initiation, and observing that across Indigenous and non-Western cultures, initiation rites almost always involve suffering—sometimes profound suffering. But that suffering is never imposed in a vacuum. Gurian notes four conditions that consistently surround initiation: safety, an elder, community, and a sacred story.

What strikes me is that safety is not a modern therapeutic invention. Long before neuroscience or trauma theory, cultures understood something essential: suffering without safety can be traumatic; suffering held within relationship can be transformative.

Initiation was not random cruelty. It was contained. A young person knew they were seen, accompanied, and held within a larger meaning. There was a story that made sense of the pain. There were elders who bore witness. There was a community waiting on the other side.

That is not fragility. That is formation.

By contrast, much of what we now call “grit” is simply unaccompanied suffering baptized as virtue. The message is: endure it alone, toughen up, don’t feel too much. But unprocessed suffering doesn’t produce resilience—it produces numbness, aggression, workaholism, or shame. What looks like toughness is often just dissociation with good PR.

Resilience does not come from being thrown into the fire alone. It comes from knowing there is a safe haven of return and reconnection.

When we talk about creating safety for children—or for adults—we are talking about strong attachment, attunement, and practices that anchor a person in their body and relationships. We are talking about helping someone know who they are, what they feel, and that they are not alone with it. We are talking about inviting genuine authenticity rather than performance.

And here’s the paradox critics often miss: when people have this kind of safety, they don’t retreat from the world—they move toward it.

A securely attached child doesn’t cling forever to the caregiver; they explore. Safety becomes the launchpad, not the cage. When the inner world is anchored, people naturally step into risk, complexity, and pain because they have the internal capacity to do so.

They step into what I sometimes call the 1,185 chapters between Genesis 3 and Revelation 20—the long, unavoidable story of a broken world. Suffering is not optional. Loss, injustice, betrayal, grief, and disappointment are woven into the human story. The question is not whether we will suffer, but whether we will be prepared to meet it and how it will produce character in us (Rom. 5:3-5).

Trauma-informed work does not promise a painless life. It prepares people for an honest one.

Safety and suffering are not enemies.

They are companions in the work of character building—and ultimately, in the work of Christlike transformation.

_________________________

Thank you for these beautiful informed words about safety and suffering.

Your reflections just took me back in my mind to the story of those 3 men who were thrown into the fiery furnace…what could only be described as an “unsurvivable experience of suffering”.

We all know the biblical “right answer” the “right perspective” that these 3 men were not alone, but in fact, God Himself, was that fourth person in that fiery furnace with them.

But for the first time, I see from your reflective thoughts, how these 3 men endured this “unsurvivable trauma” because of the safety of the one person who was present with them.

Your reflections put on a whole different light to help provide better clarity and understanding of how important “safety” is with anyone of us who is or will be suffering, regardless of why we may be suffering. May we become a person of safety in someone’s life who is experiencing sufferings! Thank you! Blessings!!

Yes. You are absolutely writing words of great foundational truth for living and thriving and impacting this broken world with the Kingdom of God. Shout it from the mountain tops!